But First, Vision.

Why articulating a vision is so important, what stillness can do to pave the way for greater empathy, and how slowing down and moving fast creates better designs.

I rarely, if ever, do much of anything before that first cup of coffee. The t-shirt tagline “But First, Coffee” is not so much a preemptive response as it is a prologue for an extended internal monologue. It is my gateway drug to how I ease into the day, how my mind shakes off the dreamy haze of slumber, and how it extends those first few still post-sleep moments. It is a ritual that comes with slight variations, filled with interruptions galore — A dog barking, a cat needing a new can of food, a stiff neck from an awkward night sleep. And yet, it’s also, predictably, a habit that grounds me (pun intended), and sets my course for the day: first on myself, then on what’s happening around me, and finally on the day ahead.

Well, you can probably guess where this is going. The parallels between the benefits of that first cup of coffee to the need to slow down and plan out any creative project is clear. Pausing for coffee is a forcing function to slow down, bringing with it awareness, calm, clarity, and dare I say greater empathy — more on that later.

For creative projects, instead of coffee, it is but vision that mimics the effects of coffee, helping set the direction for the work ahead; from the exuberant beginning, to the messy middle and finally landing on the picture you had formed in your head. So when you hear “can you mock this up?”, take a break, pause, and say “Sure, but first, vision.” — to yourself for starters, then to them.

What is Product Vision?

When it comes to creating art that touches the senses, such as music, architecture, and film, vision is a fairly easy concept to understand: it is embodied in the thing itself, how it’s experienced, and its attributes. Vision comes from the latin root vis which means “to see.” In product-speak, vision is that thing we want to see in the world in the future. It’s the answer that most often follows the question, “how might we?” It’s for all you time travelers out there trying to describe what you just saw. A good example comes from Steve Jobs back in 2001 at MacWorld when he said the desktop would become the “digital hub for our emerging digital lifestyle.”

In any creative effort where you’re inventing something, be it a new technology, product or movie, vision is that thing a team can rally around.

Painting is a blind man's profession. He never paints what he sees, but what he feels. — Pablo Picasso

Vision inspires as much as it informs. Like dreams, it imagines a world in the future that we want to see, but which does not yet exist.

I have a dream that my four little children will one day live in a nation where they will not be judged by the color of their skin but by the content of their character.

— Martin Luther King Jr

Pause Before Moving

The dictum “slow and steady wins the race” is counterintuitive in a world of “move fast and break things.” But the reality is that they can co-exist when there’s a shared vision in place. Without a clear-eyed view of where you’re going, you’re simply moving fast and breaking things. The minute you have articulated a picture of how the world will change and be different, you want to get there as fast as humanly possible. Breaking things along the way is not only inevitable, but essential. The hope is that you don’t hurt others in the process. It reminds me of another wildly held entrepreneurial saying that it is “better to ask for forgiveness, then for permission.” This is especially true when the alternative is slow and bureaucratic (Uber comes to mind).

When a child learns to walk for the first time, they’re bound to fall down, break hearts, and simply make a mess of things. But after enough things have broken off, only then can you walk, can you jump, and go on to the next challenge.

Your reason and your passion are the rudder and the sails of your seafaring soul. If either your sails or your rudder be broken, you can but toss and drift, or else be held at a standstill in mid-seas.

For reason, ruling alone, is a force confining; and passion, unattended, is a flame that burns to its own destruction. - Khalil Gibran

The practical thing to do, Gibran continues, is to “rest in reason and move in passion.” The pause helps give way to seeing the road ahead just a bit more clearly, allowing us to zoom out and see the big picture so we can zoom back in with more clarity. It gives us just enough space to be a bit less reactive and more strategic in how we tackle a problem. As Daniel Kahneman argues, we spend more of our time thinking fast (using our unconscious, mental, reactive shortcuts to what we see) vs thinking slow (leveraging the more deliberate, reasoned side of our brain). Pausing helps us think slow so we can make better decisions when thinking fast.

The Empathy Paradox

Empathy is not something you can easily acquire, yet it’s essential when designing for people. Sadly, apathy on the other hand is far more common, and easier to identify. The reason is that empathy requires work, hard work. To feel with someone else requires literarily walking in their shoes, not just once but long enough to experience the social, behavioral, and emotional toll of that person. That’s why one of our core beliefs is that you can’t tell someone to have empathy. It’s not a task that can simply be given to another person, but something that must be experienced.

But there are ways we can increase our awareness of the feeling of others, and that is to reduce one’s stress level. There’s research showing that our empathy levels go way down when faced with external stressors:

Previous studies on the correlation between empathy and stress have shown that higher level of distress leads to empathy decline—a trend that is also observable among medical students and tends to be consistent even after graduation

The magic behind the approaches of Design Thinking and Design Sprints is that they allow people’s empathy to bubble up. With the right atmosphere, including workshops, whiteboards, an enthusiastic moderator, and colorful markers, you can’t help but de-stress. The “Yes and” mindset is a possibilist one, a stress-free environment where there are “no bad ideas,” where our empathetic selves can shine, making the “How might we” exercises possible.

Sustaining that mindset is always the challenge. Enter the idea of a well-formed vision, one that helps tie things back when things get stressful.

The Calm Before the Storm

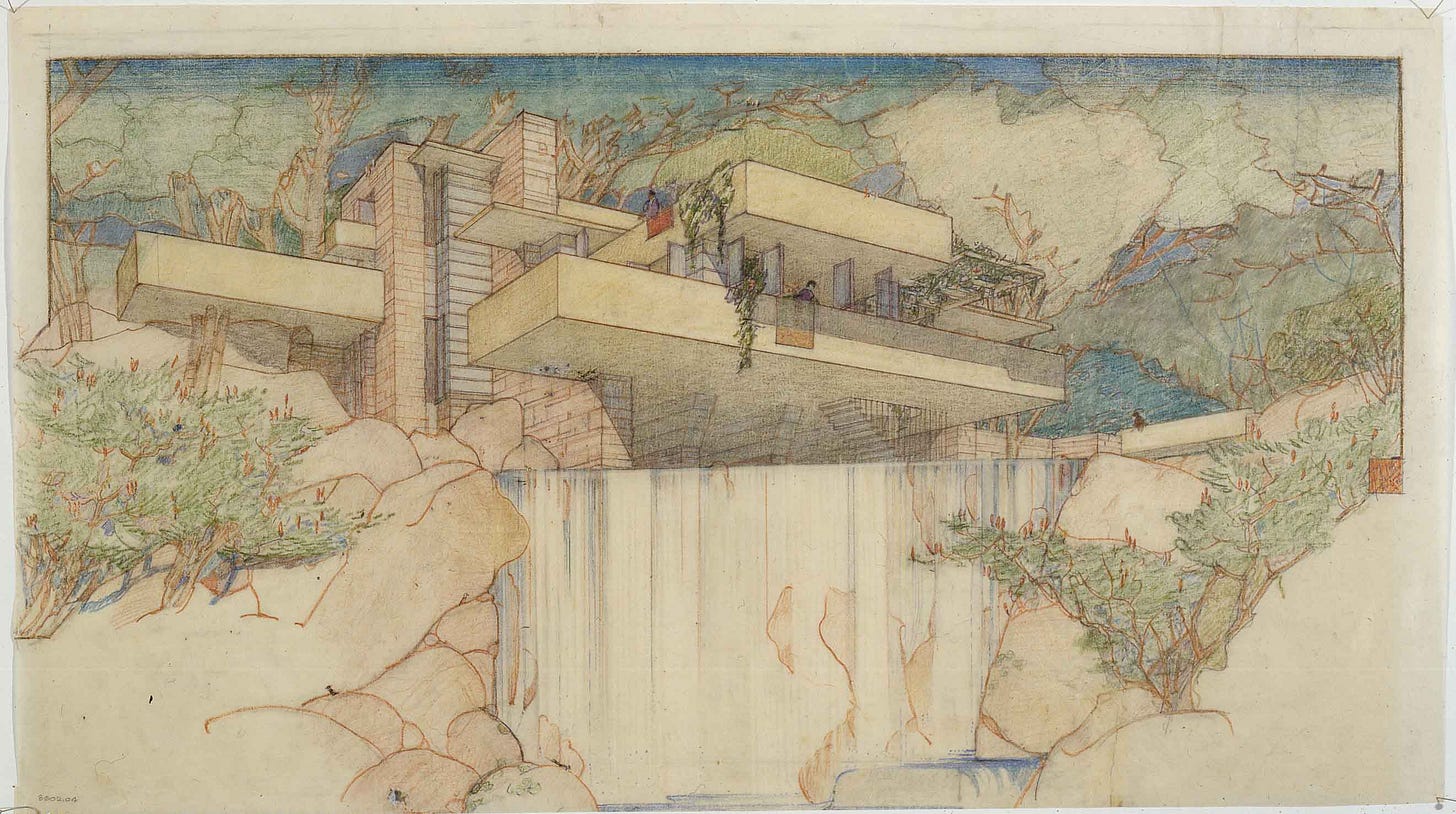

In design as in architecture, there’s a gestation period when you’re doing more thinking than crafting — in other words, slowing down. You’re essentially tinkering in your head, making to know, playing with different ideas. At this point, your subconscious is on overdrive, helping inform your taste and intuition. The quiet period gives you the space and time to process the challenge you’re facing. It is said that only after pausing (for 9 months, the myth goes) did Frank Lloyd Wright sketch possibly the most famous 20th century home, Fallingwater.

And yet that example also shows the value of stressors, because the sketch only happened when there was a deadline — the client insisted last minute to come over and see some progress on his commission.

Creativity comes from the pull and push of stress and de-stress activities, acting together to create just the right level of tension to translate vision into something tangible. It needs the metaphorical storm (the deadline) to add stress to deliver on the vision. Otherwise, it simply swirls in your head without an outlet. Stressors also break things. Sending out your ideas (rough and unfinished as they may be) for comment is akin to a child trying to take their first step, and falling. It exposes you to possibly breaking things, even your ego. But the more you fall, the closer you will gain the ability to walk. Without the stressor, your idea is forever fragile, where even walking becomes a chore.

Getting to Antifragile

Designers love to sketch out ideas. It’s how we give the smorgasbord of ideas legs, and how new ideas come to be.

How many times have you written a design brief or an email only to stop before sending, examine it the next day with “fresh eyes,” and think to yourself, what was I thinking? That’s the dumbest idea ever. The best way to avoid bad ideas is to create all the so-called good, bad, and ugly ideas you have and slowly winnow them down to the good ones. And by good ones, I mean the ones that best meet your original vision — whatever that may be.

Nassim Nicholas Taleb has coined the concept “antifragile” to describe things that gain from disorder. These are things that when they meet external stressors, they actually become stronger, better. Examples are the human muscle (exercise stresses muscles causing them to grow), forest fires (destructive short term but becomes more fire-resistant in the future), and cast iron pans (the more you use them, the better they get).

Why do we want our designs and ideas to be antifragile? If nothing else, we want them to stand up against any pushback that comes at it. Armed with a lot of failures, we can point to reasons for why a specific direction failed, or why it doesn’t meet the original vision, be it a business goal, problem to solve, or user experience attribute. By being able to withstand any and all criticism, it will only strengthen your hand at getting buy-in to deliver on your vision.

But there’s a point where too much stress is damaging. Just like grapes need stress to produce great wines, too little water or too much, at the wrong time, will reverse the gains and ultimately damage the vine. Just ask a viticulturalist: the key is knowing when and where to apply the stress, the skill to know how, and the vision to know what it needs.

Shared Vision, Shared Language

Imagine starting to shoot a film without a storyboard, or a strong sense of what the director’s artistic vision will be? Designers are at their best when working within constraints. Without a well-formed product north star, the team is quickly unmoored, floating here and there, grasping at different emergent ideas that do not align with the vision. It can easily become a game of Whack-a-Mole, with people’s time most often getting whacked. No coherence, leads to no cohesion, and ultimately to no commitment.

The nature of new product development efforts is that they invariably spin off into additional, related problems. These begin to branch off like a tree in more and more issues that each require focused attention. It’s complicated enough…no need to over-complicate it further.

For that reason, it’s important to spend time upfront to work backwards, from the vision, to help set the overall direction for the team. A single product vision makes everyone play by the same playbook, tackling the same problems – climbing the same tree if you will – yet always tracking back to the original vision. Without this collective ability to backtrack, even the best ideas will not make sense for the problem at hand.

Agile makes this pattern worse. In the absence of a coherent vision, the product starts to iterate in different directions, fractal like, bouncing to unforeseen and ultimately undesirable places. Even Kent Beck, one of the lead authors of the agile manifesto, argues that agile works best when everyone is shooting for the same north star, iterating as they move together.

Product vision, combined with a clear, compelling user experience, is what separates effective teams from the rest. It creates a narrative, a spark that inspires and informs creativity — something that competent designers naturally gravitate around.

What Vision Looks Like

In truth, vision can look like anything. What’s important is that it is:

Memorable

Easy to understand

Exponentially better than today

The format of that vision can come in many forms, from a PRD, mockup, prototype, product design brief, or even a fake press release of that future product.

I prefer a combination of mockups plus a few attributes of the product. This approach leverages the power of visuals — “a picture is worth a thousand words” — and then distilling those “thousand words” it into a few memorable takeaways.

For example, for Figma it is: 1) Collaboration in real time, 2) intuitive enough for anyone to design, and 3) easy to handoff designs to developers. For the Apple Airpod, it is: 1) Amazing sound quality, 2) beautiful to wear and well designed, and 3) long battery life.

Do others come to mind? Leave in the comments below.

How to Articulate Vision

Vision is caffein for creativity. Yet most product managers suck at both design and vision, with some exceptions of course that prove the rule. It is not their strong suit. They often get projects funded based on the goals they’re trying to achieve, business goals, and problems being addressed. Most cannot articulate the vision or even the concept they’re trying to build, or will point to a competitor site or a similar example as their north star. This fails because real vision, the one that helps inspire and get people excited, is usually not derivative. It is original, based on the unique and context-specific problem.

Where product managers and designers can and must collaborate, however, is on the attributes of the product. This begins to form the outline of vision, the constraints that define the contours of the final design. It’s not prescriptive, but rather it outlines the key takeaways we want our users to appreciate, the attributes that make it stand out.

By stopping and working together, design and product, to lay out the product vision, everyone benefits by helping to define the roadmap and experience. And perhaps more importantly, it helps make the product just a little less fragile when it finally hatches and begins to walk on its own.

Invite your friends

If you enjoy The Experience Architect Newsletter, share it with your friends.