How to Give Feedback to Designers

Turning feedback into a conversation, not a critique

Ever notice how often people hesitate before giving creative feedback, even though it’s the most instinctive reaction? The impulse runs deep. Giving effective feedback asks us to modulate between thinking fast and slow to make sure the feedback lands as intended. But blending those two modes is much harder than it seems.

How we think about feedback, both as the giver or the receiver, sets the tone for how effective it will be. The common mistake people make is to think of feedback as one directional, rather than what it is, a conversation. Beginning any other way triggers the very knee-jerk reaction you cautioned against when giving the feedback, despite your best intentions. Only through a dialogue, even a brief one, can you begin to approach the problem that you both are seeking to tackle.

The best feedback has three things in common:

Mutual trust.

Feedback is viewed as a gift.

Focused on solving a shared problem.

When these elements are present, feedback moves the conversation from a state of worry to wonder.

Trust

Why is it so important to lead with trust? For starters, trust helps put the human receiving that feedback at ease by reducing the potential bluntness of a perceived critique. For good reason, people are naturally apprehensive about receiving (and giving) feedback. By building trust quickly, we’re able to meaningfully foster honest, constructive dialogue without fear of judgment.

The mistake is to assume that your good intentions are good enough.

The goal of any effective feedback is to be heard clearly and processed thoroughly. Trust ensures that what you’re hearing is coming from a good place, implying that there’s some value to be shared in the conversation. Even taking in the actual feedback, hearing what is being said, is the first to go when trust is lacking.

While trust may seem an obvious starting point, it is rare and often taken for granted. The mistake is to assume that your good intentions are good enough, or that your official title or experience bestows the honor of “Trust me.” Even when it is safe to trust, we humans have learned to trust but verify. How do people verify? Through words and actions that make the encounter less personal, less confrontational, and more like a partnership.

In design (or any creative field), the personal dimension of feedback makes it even more important to understand how effective feedback works. Unlike technology, where objectivity reigns (the computation either runs or doesn’t), design has a strong subjective side, bleeding into things like personal taste, style, biases, cognitive load tolerance, and simple aesthetic preferences. And neuroscience goes even further, with research showing that all these aspects of design are tied back to one’s identity.

So when the designer creates something, it’s always personal, arising from the part of the brain that is core to who we are, shaped by everything from our memories and perceptions to feelings and emotions. And that’s where trust comes in to remove the slightest notion of a personal attack, and ensure that feedback is not feared but sought after.

One of the many gifts that Steve Jobs had was to transform design from something purely aesthetic (its form) to functional (it just works) without dismissing the importance of having a design point of view.

A common mistake in design feedback is not knowing what you want. It sounds fundamental, but it turns out that knowing what you want is a lot harder than knowing what you dislike. Without knowing the goal, design feedback gets stuck in superficial commentary without stepping to address the shared problem.

One of the quickest ways to build trust is by showing confidence through your enthusiasm. Why enthusiasm? For starters, it says you want to make them succeed. Just as a cheering audience boosts a comedian’s confidence on stage, enthusiasm is both contagious and invigorating. It fuels creativity and makes it clear that feedback is being given as support, not judgment.

Frame the discussion to make feedback feel less like an ominous checkpoint, and more like a reststop on the path to creative exploration.

One of my favorite techniques is to add humor and humility to increase connection (essential for a productive dialogue) and raise the level of trust. That’s why self-deprecating humor — and humor in general — is such a powerful tool. It reveals trust by preemptively exposing faults with oneself, implying to the recipient that I trust you not to “weaponize” my faults. When Ryan Holiday says in his book, “Trust Me, I’m Lying: Confessions of a Media Manipulator” you can’t help but believe him. Combining humility with transparency is one of the most powerful recipes for earning the trust of others.

Gift

Looking at feedback as a gift shifts the focus from critique to collaboration. This mindset does two important things:

It turns anxiety into curiosity — who doesn’t like to unwrap a gift?

It invites connection and reciprocity.

Turning feedback into a gift is not just optics; quite the opposite. It makes future interactions stronger and more likely to happen. By engineering feedback into everything you do, feedback becomes something you seek out rather than avoid. This can be encouraged by simply asking for feedback more often and normalizing a culture of feedback. And like most interpersonal things, it’s a learnable skill that requires constant reinforcement.

The reciprocal side of feedback has huge upsides. While designers are often anxious to hear feedback about their own work, ironically, they’re often the biggest advocates of feedback from users.

When giving feedback, it’s important to view the design as a work in progress, to leave the door open to make a mark on it. People often value something more if they had a hand in creating it — and this in turn helps both the designer and the feedback giver get closer and more connected to solving the problem.

IKEA built a retail empire by selling on this human tendency — inexpensive furniture feels more valuable simply because we brought it to life. Positioning work as unfinished leverages this IKEA Effect, giving the feedback giver a sense of ownership they wouldn’t have felt if it was presented as final.

The notion of creating something that invites others to shape it is not a new idea. The Japanese concept of Ma (negative space) is an approach widely used in traditional Japanese architecture and tea ceremonies. This negative (or empty) space becomes an opportunity for the person entering it to project their own emotions (and feedback) into the space, helping to increase the connection with it.

Ma plays an important role in another way. By creating (empty) space, it allows for a different kind of pause, one designed for reflection and patience. Unlike extroverts or linear thinkers, designers need some space to think. Their cerebral nature compels them to seek out time to fully process feedback, sometimes hidden in the recesses of their unconscious. That’s why it’s useful to let some time pass after giving feedback to let it sink in — sometimes overnight — to allow space for rumination and thinking through the problem.

To better grasp the concept of Ma, think back on how it felt to stay at a cluttered home that was not yours, filled with other people’s stuff. It instantly becomes clear that the space is somehow set apart, leaving little room for you to make a connection with it. This is the main reason why the best Airbnbs lack any sign of the owner’s fingerprints, let alone actual fingerprints, of any kind.

Another mistake people make is to create too much emptiness in the form of not enough background or relevant information. One of the biggest areas is not being clear on the assumptions that frame every discussion or design review. Like a poorly picked out gift, making the wrong assumption can lead to things backfiring, like giving a vegetarian a gift card to a steakhouse. Reiterating assumptions goes a long way to provide guardrails around the conversation so things don’t go off track.

Empathy

In the world of design, empathy is a word that’s given a lot of lip service, but sadly far too little of it is meaningful. The conditions that enable real, actionable empathy are far too rare, too personal and experiential by design. While empathy is hard to find in others, empathy in action is even harder. It is this kind of active empathy, which the Japanese call Omoiyari (no English equivalent), that drives effective feedback in two key ways: empathy for the designer, and empathy for the user with the problem.

Empathy in both cases, for the user and the designer, share things in common: They start with noticing so that the feedback-giver understands context, motivation, and intent. It shows that you care about the user and the designer in equal measure.

For most digital products, vision is what you would like to see in the world tomorrow that doesn’t exist today.

What are the best gifts you’ve ever received? My guess is they’re a version of Omoiyari at play. Memorable gifts, like good feedback, reflect a deep understanding of your personality and what you need, they come from a place of care, and leave space for you to make it your own. Without empathy, it’s nearly impossible to give a meaningful gift, the fundamental part of good feedback.

Vision

A movie director gives lots of direction. You can even say it’s their main job. When observing a director in action, it seems straight forward. The director gives instructions to the actors and crew on the set, with multiple takes to get it “just right.” And yet great directors know that not all feedback is alike, and getting the most out of your team separates the good from the bad directors. What’s more is that the crew, and especially the actors, simply want to know what the director wants. Which is why it’s so difficult to give effective feedback without knowing what you want. Without a vision, feedback feels arbitrary, or worse, personal.

The short clip below is a good illustration of what makes a good director:

Most feedback is given by people who don’t have a strong vision. That’s normal and predictable. But it’s important to caveat it upfront, or briefly ask the designer what they were hoping to achieve, which is a close proxy to vision. You can then use that image as a baseline to inform your feedback about whether the work met that vision.

And you might say that effective feedback is not rocket science. Actually, it is. The term was first popularized in the aerospace industry to help guide rockets to their target. The rocket sensors would send information back to earth about things like position, speed, and external conditions, and people on earth in turn would give feedback to keep it on the right path; a conversation between humans and their creation.

Vision can take many forms. Sometimes it’s aspirational. For Google Maps, it was “Never Get Lost Again.” For others, it could be more visceral, sounding more like a mission statement. A recent example is Stripe’s mission to “Grow the GDP of the internet.”

For most digital products, vision is what you would like to see in the world tomorrow that doesn’t exist today. It’s like a time traveler returning from the future they just saw and trying to describe it. Often, the vision narrative describes the “why” and “how” of solving the problem, not the “what.” Directing everything toward that goal becomes the most important thing, and how to achieve the “what” up to the team to figure out.

Another mistake people make is confusing vision with being a visionary. Visionaries are rare, vision need not be. And that’s because the process to create a unifying vision is nearly always a team sport and rarely a solitary effort. It takes a team, working together, to iterate and executive it to make that vision real.

In the book Make to Know by Loren Buchman, the author explains that while Steve Jobs had the original idea for Apple Stores, the final design (or vision if you will) came much later. It took collaboration with a skilled team and multiple rounds of creative iteration—often using life-size store prototypes—to develop the Apple Store we know today.

How do you achieve a semblance of vision? No secret recipe aside from combining empathy, enthusiasm and creativity to help shape it: Empathy to anticipate needs, enthusiasm to persist, and creativity to iterate.

Praise

Praise is an often overlooked type of feedback, especially with creative work, where it doubles as a powerful motivator. Mark Twain once said:

I can live for two months on a good compliment.

When you’re presented with a creative work — be it a work of art, a user flow, or design system — there is always going to be things that you like, dislike, or things you are simply curious about. Edward de Bono took this idea further and applied a framework that helps design reviews avoid paralysis by analysis.

He would solicit feedback to an idea by asking participants to respond with things that they praised (positive), things that were negative (or minus), and things that were interesting (PMI for short). Instead of focusing solely on what's good or bad, the process highlights ideas that might seem odd at first but could turn out to be the most worthwhile to explore. This is useful because often it is at the edges of these peculiar ideas where the seeds of a great idea lie dormant.

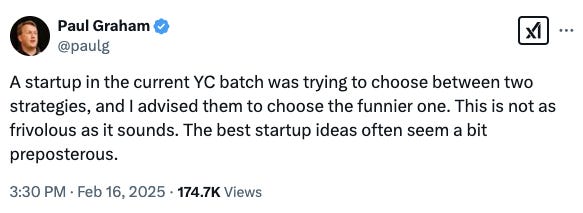

If you look at ideas in this way and think “I wonder…”, you open your mind to think of alternative ideas based on all your other half-baked ones. Try this at home: Observe something around your house or neighborhood, and start the sentence with “I wonder…” and see where that takes you. That’s the power of observation and giving effective feedback. It’s the improv equivalent of “Yes and.” As Paul Graham noted, if you have to select between two different ideas, choose the funnier sounding one — it’s often the one that will be the most interesting to push forward.

Doc Rivers, the famous NBA coach, once said that “Average players want to be left alone Good players want to be coached. Great players want to be told the truth.” The art of feedback lies in separating the personal from the objective, offering just enough critique to nurture growth without uprooting the roots.