Ten Harsh Truths About UX Design

And some proven tips to get past them.

There are many wonderful and beautiful things about being a designer, especially UX design. One reason I left urban planning to be a designer was UX’s immediacy. It gave me the ability to quickly test out my ideas, easily sit with real users, hear their problems, and create solutions they can use. Unlike city planning and urban design, there was very little bureaucracy (no zoning variances or permit review sessions), and the timelines for getting something built was solely dependent on how quickly you could code or put pixels on a screen. You could measure the results in hours vs years.

But with those perks came some harsh realities, which have only worsened as the industry has matured. I thought I’d share some “truths” to help anyone considering entering the field or second guessing their chosen path. As you’ll see, it’s not all bad news. It’s followed with some practical tips to overcome and thrive in the face of what seems like insurmountable odds.

So, here we go… some harsh truths about UX design:

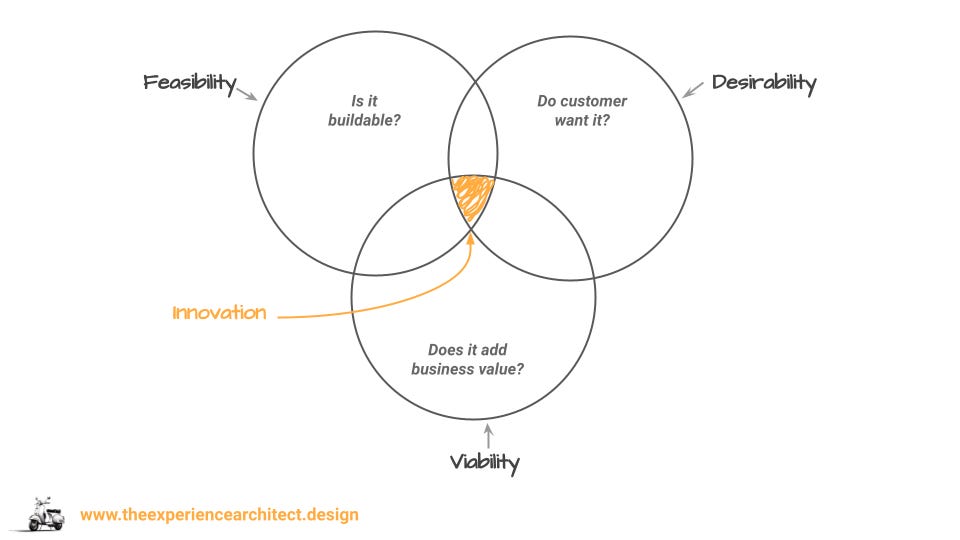

1/ Feasibility over desirablity. Designers love to speak about creating experiences that delight. However, it’s a lot harder to know what people want than to know what is possible to build within a certain artificial timeline. In truth, tech and time dictate feasibility, while desirability is finicky to measure. User research helps, but its limitations are well documented. Knowing what’s desirable often happens only after users see it working in action. Desireability then becomes an infinite game and a moving target, changing over time. Iteration, tinkering and experimentation for companies becomes a more certain barometer to help uncover the illusive goal of desireability. But this requires working code, working in the exact fashion a designer hoped it would — a rare scenario.

2/ There’s less to design. The canvas, the actual screen real estate that designers have to work with, have been getting smaller and smaller every year. November 2016 was a pivotal moment in web traffic, where mobile traffic equaled that of desktop. Today mobile accounts for nearly 60%, while desktop is 37%. When you combine this with mobile-first responsive designs, our collective shorter attention spans, and more reliance on visual communication, the need to spend time to create more stuff, more graphical elements, is also reduced. Design frameworks, design systems, best practices, and style guides provide the foundation for most designs today, leaving little room for designers to design.

To illustrate this point of the shrinking screen size, below is a timeline view from 2010 on showing people accessing the Web via Desktop (in purple) and Mobile (in green). Around 2010, with the iPhone about 3 years old, desktop percent usage was in the high 90s, with mobile barely registering a blip. Fast forward six years later to 2016, it was 50-50. Mobile has not looked back since.

3/ Design strategy is product strategy. Unlike UI design, higher level UX hits on the core of the product and business. In many circles, it may be called product discovery, incorporating research and experimentation, but in truth, it’s not about design, but rather about product strategy. Design strategy ends up becoming a subset of product strategy, with product driving much of the experience. Designers are left with making it “look pretty” and working at the edges, instead of the core experience itself.

The moment a design is influencing user behavior — removing a feature, suggesting an alternate approach — it becomes product strategy. It’s no longer about just pure customer experience, but about what the business values. The 5-year Google Search trend proves that out… most people are more interested in product strategy than with design strategy.

4/ AI is already driving much of UX. With algorithms, 1:1 ads, personal feeds, automations, and recommendations, what a user sees is increasingly predictive rather than prescriptive. With AI also comes a loss of control for UXers, where design decisions are made not by humans but by data-rich, large language models (LLMs) making billions of computational instructions per second. This far exceeds any group of humans to anticipate, curate, or design a better experience. And if you factor in GenAI, which attempts to predict the next word/feature/action based on context, this is not unlike the creative process that UXers attempt, but with far less data.

5/ Good UX is invisible. Advocating and explaining a design decision is part of the job. Another harsh truth, this time embedded in another harsh truth. No matter the amount of experience or credentials you have, design is partly a beauty contest, part personal taste, and mostly subjective. Even with a seat at the proverbial table, UXers must work to earn the trust of others. Why? Because it’s both invisible and subjective. There’s a heuristic, sensory, and aesthetic dimension to the judgements, which is earned with lots of hard work and trust building.

6/ True empathy is rare. UX is rooted in the school of Design Thinking, an approach grounded in empathy as the driving creative force of design. And yet, real empathy is an ideal that can never be fully met. Everyone’s experience is different, and there are many things you’ll never truly understand unless you personally have experienced it, no matter how empathetic you are. Walking in other’s shoes is a fantasy that’s rarely possible and hard to measure. For one, as Nietzshe reminds us, it requires an ability to experience another’s pain as if it was your own without losing perspective in the process.

7/ UX is about experimentation. It’s less about art, and more about the scientific method. As such, it’s about having a hypothesis rooted in a user problem, the space to create multiple versions to test, iterate and repeat. The work of UX is never finished, but a point in time, constantly evolving as you receive more and more feedback. Over time, new and different hypotheses arise, requiring a different approach that needs more experimentation to validate.

8/ You have a client, but it’s not the user. Rather, your client are the people you work with — your manager, engineers and product managers — who will evaluate you based on how well they like working with you. Harsh? Yes, but true for many other creative pursuits as well. Graphic designers ultimately have to please their client first before their intended audience of their work. Architects are in the same boat. While it’s true that repeat customers come back because of the design’s performance, with UX, it’s rare to get results within a reasonable timeframe for anyone to remember, or to receive credit for what ultimately is a team effort. Unlike an artist or graphic designer, rarely do you see a UXer’s name on their output, or getting credit for a specific experience or feature. Design is a team sport, a sport in which credit is not bestowed on the individuals on the team (maybe in passing), but in the product owner who gets the most credit for its success (and failure).

9/ Everything you create will be changed. The process of designing technology is from creating art or a piece of music, where your creation relies exclusively on your own handiwork. UX designers are more like Wikipedia authors, where everyone and their sibling will chip away on the smallest points, revising and disputing key parts of the design, navigation pattern, button labels, and experience. And like Wikipedia, editorial consensus is the norm, unless your name is Steve Jobs.

10/ Pure Agile co-opts design. This last harsh truth has to do with the environment that UX operates in. Agile was designed as a framework primarily to improve the quality and quantity of software development, by engineers for engineers. Its emphasis on execution, as a result, forced design to be reactive. Where once development teams relied on designers to deliver the vision and spec for a project, agile enabled engineers, product managers and business heads to call the shots, with design riding shotgun. Where once design was the creative director and producer of the end product, it now has to hitch a ride to make an impact. Further compounding this was the byproduct of the popular minimum viable product (MVP) approach. Over-indexing on building the MVP reduced the need for upfront design strategy. This paved the way for a more concerted effort to create an overall product strategy, one that was informed by many factors, including the user experience.

All these harsh realities worsened as talented designers got promoted to managing up rather than down. The remaining designers were often ill equiped to collaborate effectively with more senior product and engineering leads. The UX field itself became more about stakeholder management and power struggles rather than design as craft. It became viewed as more of a production function, a thing to work on as needed, and optimize if the right circumstances came about.

These harsh realities are here to stay. But there are a few things you can do today that softens the edges of these truths, while placing you in a position to be an effective design leader and contributor.

Tip #1: For starters, a sense of humor is essential to keep team levity up (whom you’ll need to stay inspired and curious), as well as brush off confrontations and disagreements. A sense of humor is also a reminder to not take ourselves too seriously, while connecting with others.

Tip #2: Have a strong point of view, but ensure that it’s loosely held. You won’t always have a strong point of view, but it’s important to do the legwork that will allow you to have a decent hypothesis or view of what the future should look like. Creatives are uniquely positioned to do this as the very essence of design is to create something new. Just as important, that point of view cannot be held with such certainty that you resist hearing perspectives of others. The more you can be both bold and flexible shows to others that you’re curious, prosocial, and open to new information.

Tip #3: Related to tip #2 is to surround yourself with people you disagree with. Not only does it help you learn new information and perspectives, but for your sanity, it helps build the capacity to disagree agreeably.

Tip #4: Build strong relationships with people. Design is a relationship business. Not only do we design for others, but we need others to get our designs out the door. It’s a truly collaborative activity, and the stronger your relationships are with others, the more they will trust you, understand your motives, and your skillsets.

Tip #5: Patience is indeed a virtue. Meaningful design takes time and effort to get it right. Designers have to be advocates playing the long game, dreamers and doers, collaborative and ambitious, willing to diverge and converge equally well to solve a problem. Figma, designer’s new favorite tool, is one such example of patience at work. Founded in 2012, Figma only started shipping software to beta users in 2015. It then took another two years to add paid plans. It’s part of the creative process. If it wasn’t hard, then everybody would be doing it. This is one cliche that will always ring true.

I’m debating whether or not to share this with a young man I just met. He recently graduated from uni with a degree in HCI.

Would it help if he were forewarned and forearmed with these valuable insights? Or would it make him think “I chose this wrong profession?”

As for myself, waiting on the sidelines, considering myriad personal futures, reading your missive gave me terrible flashbacks. Everything you wrote is 100% true.

The Lucy and the Football trope*?comes to mind when MVP is mentioned. “We know the product falls far short of what user research tells us they want. But don’t worry we’ll address these issues after launch.”

* A recurring skit from the Peanuts cartoon. Lucy would hold a football up for Linus to kick but would yank it away at the last second, causing him to flip over. She’s laugh and he’d lay there wondering why he (literally) fell for her trick again.